If we are not able to do what machines can do, then why not to trust them? – asks Marek Kozłowski, co-creator of the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System

Robert Siewiorek: Do you remember Molière’s The Bourgeois Gentleman? Aspiring to become a member of the elite, Mr. Jourdain, a parvenu, is taught oratory skills by a philosophy master. He wishes to send a letter to a women he is fond of and he wants it to read: “Beautiful marchioness, your fair eyes make me die with love”, but he wants to put it in a more gallant way. The master then suggests altered versions of the message, for example: “Me make your eyes fair die, beautiful marchioness, for love” or “For love die me make, beautiful marchioness, your fair eyes”. Would I trick your system if, similarly to the Moliere’s character, I changed the word order in a text I would claim to be the author of?

Marek Kozłowski*: No, because our anti-plagiarism system is completely immune to that. Changing the word order wouldn’t result in making the system impossible to identify a quoted passage. The system divides a text into sentences; the sentences are then divided into words which form non-organized collections.

Collections?

Sets of elements, and not their lists. So if we write: “Mom likes cats” or “Mom cats like”, in both cases the system will see three different words in two sets, each of them being equivalent to the other one. Crossing those sets is the measure of probability. In our example, the system would return information on discovering a 100-percent plagiarism, because both sentences include the same words.

Does it mean that, no matter how good I am at syntax, if I steal someone else’s text, I will be caught anyway?

Yes you will. Our algorithm is immune to changing the word order in sentences, letter case, and punctuation. It cleans the analyzed text to use it to build unambiguous sets of words, single tokens, and to work on them.

Does the system treat words as construction elements or does it understand their meaning?

In a way, it understands the meanings, because it sometimes uses thesauri. For instance, it knows that “automobile” and “car” mean the same. However, the semantics framework within which it operates doesn’t allow it to recognize the words “adore” and “love” as synonyms. Technically speaking, it is doable, but then the algorithm would be too sensitive as it would associate words that are not equivalent in terms of their meaning.

What do you mean exactly by saying “system”?

The Uniform Anti-plagiarism System (Jednolity System Antyplagiatowy – JSA), which was developed by the National Information Processing Institute in Warsaw, where I work. It is an IT system which aids supervisors in identifying plagiarized bachelor’s, engineer’s and master’s theses. In May the system will also be able to handle doctoral theses.

Are we referring only to the theses published after or also to those put out before the implementation of the system?

Only to those scheduled to be defended after 1 October 2018. Similarly to the rules of law, the system is not retroactive.

How many theses has it already surveyed?

In January and February it was used to carry about 40 thousand surveys; in the case of over one thousand theses PRP was very high, reaching 70 percent.

PRP?

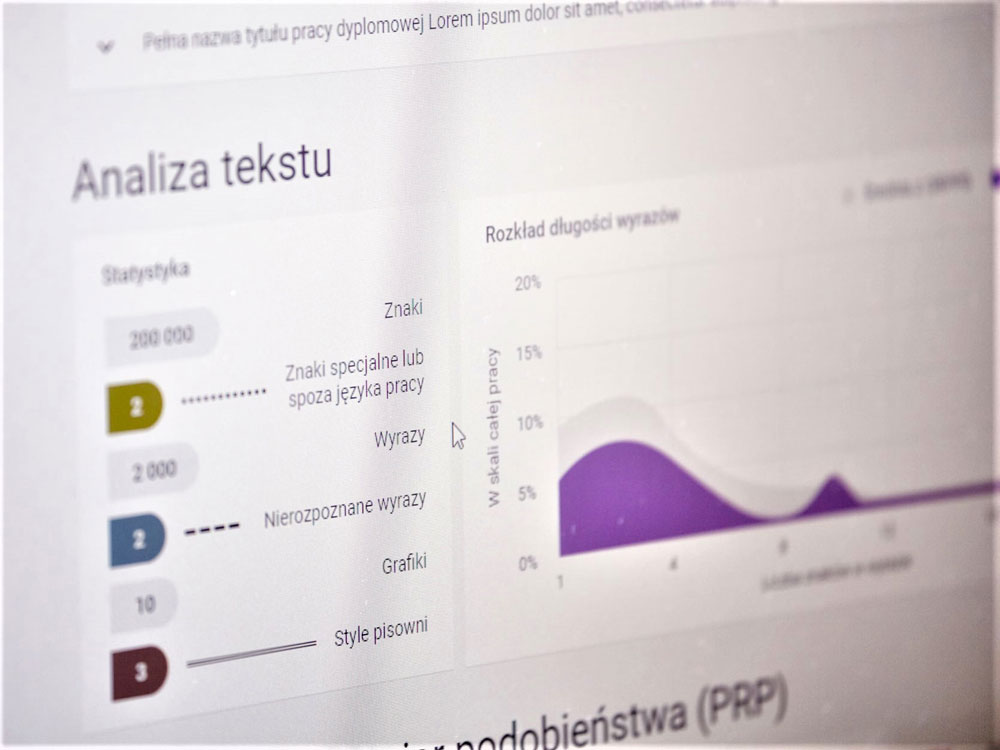

It is the Polish abbreviation for Percentage Similarity Rate. The system can count the percentage of passages included in the text that are similar to the passages used in other publications. For example, let’s say that in a thesis I have discovered the total of three separate passages each comprising 30 characters, which would bring us to the total of 90 characters in plagiarized passages included in the thesis. If we divide that result by the total number of characters in the thesis, we will get the PRP result. In other words, it shows what amount of text in a theses comes from other publications.

The system divides every surveyed document into text windows (e.g. five sentence chunks), uses them to create a kind of microducuments and then tries to find similarities. When it identifies a similarity, it refers to the original document. The number of such five sentence microdocuments at our disposal has already exceeded 8 billion.

How long did it take to develop the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System?

From 2017 to the end of 2018, which is one and a half year.

How many people were involved in the project?

About a dozen. At the beginning, we were 10, but in the end the team consisted of 15 people, including testers, developers, administrators and analysts.

Did you draw inspirations from any other systems?

Yes, we analyzed some of the most interesting features they had to offer but we surely haven’t copied anything. Our system is unique.

How big are the documents bases used by the system?

Currently, we have 11 big data bases. They include the National Repository of Theses (ca. 3 million theses), the NEKST base, which gives us the picture of the Polish internet resources (ca. 760 million documents), six Wikipedias in different languages, including Polish, and collections of legal acts.

And does the system really go through hundreds of millions of documents to look for the passages similar to those used in the surveyed thesis?

Yes. In short, the system divides every surveyed document into text windows (e.g. five sentence chunks), uses them to create a kind of microducuments and then tries to find similarities. When it identifies a similarity, it refers to the original document. The number of such five sentence microdocuments at our disposal has already exceeded 8 billion.

OK but take a look at this: “Millions, millions of tons of stone. Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries more stone was excavated in France than in ancient Egypt, the land of gigantic building structures. Eighty cathedrals and five hundred large churches built in that period, if gathered together, would effect a mountain range erected by human hands”.

And?

And now listen to this one: „In the space of three centuries, from 1050 to 1350, several million tons of stone were quarried in France for the building of eighty cathedrals, five hundred large churches and tens of thousands of parish churches. More stone was excavated in France during these three centuries than at any time in ancient Egypt”.

They sound very similar.

The first passage comes from the book entitled “The Cathedral Builders” by Jean Gimpel published in France in 1958; the second one comes from the “A stone from the cathedral” essay by Zbigniew Herbert included in his compilation “The Barbarian in the Garden”, first edition, 1962. Would your system consider Herbert as a plagiarist?

That depends on how sensitive the algorithm parameter is to similarities in the texts. Let me explain what I mean by that. It is possible for the system administrator of an institution to define how sensitive the algorithm searching for similarities should be. Should the algorithm take paraphrases into account? Or should it be allowed to only search for plagiarisms understood as exact same sequences of words? The similarity slide is a measure that can range from 0 to 100 percent. However, setting its sensitivity to 0 percent wouldn’t make any sense because every text compared with any other would be considered a plagiarism.

In other words, the threshold of 100 percent means the similarity of one to one. Is that correct?

Yes, as far as the words are concerned, although the word order may be different as in “Mom likes cats” vs. “Mom cats likes”. Or as in the Molier’s play. The value of 100 percent tells us that the sentences contain the same words and so the system will consider a text surveyed as plagiarized. But if only one word is different in both texts, the system will not discover any plagiarism issues. If the algorithm sensitiveness parameter is set to 100 percent, the system will identify only perfect clones of documents.

Clones?

The clone is defined as a passage of text copied to another text. But if you set the sensitivity to 100 percent, it will mean that you do not consider a plagiarism as anything that is connected with paraphrasing. However, if you set it to, let’s say, 30 percent, you accept a certain paraphrasing rate.

How do you set the slider?

Our default value is 30 percent. According to our studies, this value is optimal. But a university may find the system to be too sensitive. They may not be interested in finding too many similarities, which will distort the final overall picture of an author’s thesis. They may decide to set the slider to 50 or 70 percent. The parameter may differ in value from faculty to faculty. For instance, humanities faculties may be interested in the results with the parameter set to ca. 30 percent, while STEM faculties might prefer the value of 70 percent.

And what about universities?

They usually set it to 50 percent. And that seems reasonable.

Is it enough to determine that Herbert plagiarized Gimpel?

Yes. The slider set to 30 percent would be enough. Actually, I dare say that some doubts would appear even with the value of 50 percent.

Do you know any science theses that were suspected of being a plagiarism as a result of the value being set to that sensitivity value?

Yes, two. One thesis was about experiments on reinforcing solutions for ferroconcrete bridge construction structures; the other one was about plasticization of such structures. Although the system found many similar passages, the supervisor decided that the theses were not plagiarisms. That was his interpretation.

How do supervisors react in such situations?

It all depends on an individual. Many technical universities argued that the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System shows too much and that it is too sensitive. They were interested in discovering clones only. Some claimed that a paraphrase is a personal matter of an author, so they changed the slider value to 70 percent to solve the problem.

Why not to go for 100 percent?

Because such an approach would be hard to justify. It would mean that for the university only clones are plagiarisms. It would mean that if only one word is changed, the system wouldn’t be able to classify a thesis as a plagiarism. You might call it “deliberate blindness”.

What do you need to trick the algorithm? Should you be more inventive with how you use your language?

A considerable margin of manoeuver is left to those who translate passages from foreign publications. If you translate someone else’s thesis written in English, the algorithm will not be able to identify similarities… yet. But soon the algorithms will be able to detect them.

Another thing is a good paraphrase. Not an ordinary one that we can find in a dictionary or that we use to look for plagiarisms.

A literary paraphrase?

Yes. If you reformulate the original sentence “Yesterday we launched two ships.” and change it to “On Tuesday our brigade set two vessels in the water.”, the system will never detect any similarity.

What tools and procedures did the universities apply until recently to reveal examples of plagiarisms?

They had different systems, e.g. Plagiat.pl, Genuino, OSA. But all of them had limited access to data sets. Data sets usually included only the ones created by a university from which a thesis originated or by universities for which a given system operated.

Does that mean that you could copy the passages of a thesis defended at any other university and nothing happened?

Not only passages. There were times when a thesis defended in Opole was defended in Suwałki one month later.

What do universities think about the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System?

They are reserved.

Is that because revealing instances of plagiarism would tarnish their reputation?

Precisely. Plagiarism also means that the quality of education at a university is poor. It’s even worse than that. The universities we are in contact with informed us that due to alleged instances of plagiarized bachelor’s, engineer’s or master’s theses several dozens of students were failed to obtain the approval of their supervisors to defend the theses.

The percentage similarity rate of 30 percent is a problem but not a tragedy. You always refer to the idea, research methodologies, achievements and tools that were created before you

Is it a serious issue in Polish science?

It is serious, considering the fact that within only two months the supervisors refused to give their approval to several dozens of students to defend their theses. And that is only a part of a broader picture. Some universities won’t admit the issue exists in order not to reveal the real scale of the problem.

Is it bigger than anywhere else?

No, it is the same. Well, maybe except protestant countries.

Work ethic?

That’s right. Attachment to a certain quality of work rather than to its final result. Nobody wants to talk about it openly because that would reveal our ethical problems we have had for quite a time. So everyone remains tight-lipped until you show them the numbers. As long as you can refer to dogmas and visions, the phenomenon cannot be measured.

You can put it down to poetry.

To poetry, paraphrase, ill will of hostile forces. Or you can say that the problem is marginal – two cases a year, tops.

And what is the reality?

I reckon that there are about 5 percent of plagiarized theses.

Meaning that one master or engineer in twenty is a cheater…

Maybe not every single one of them is a cheater but surely each of them committed a fraud by using the source texts in an unauthorized way.

Do you like Monty Python?

A bit but I haven’t watched any of their stuff for donkey’s years.

John Cleese once said: “If you work in a creative industry, you should steal other people’s ideas. Shakespeare lifted plots from Greek classics. If you say that you are going to write something completely new, original and extraordinary but you are limited to what your mind is telling you, it’s like trying to fly a plane without having any lessons.”

Well, yeah. You always need a starting point.

Science is also a creative industry.

It is. That’s why I always say that the percentage similarity rate of 30 percent is a problem but not a tragedy. You always refer to the idea, research methodologies, achievements and tools that were created before you. When you do that, you confirm that you know them and that you know how to use them. No reference would also be suspicious.

Because it’s inventing the world from scratch?

Precisely. In my opinion, you don’t commit any crime if your thesis consists in 30 percent of references to source literature, basic concepts and ideas. But if 70 percent of your thesis shows similarities to other publications, then you got a problem.

Don’t you think that all those machines and algorithms curtail our freedom of creativity? Don’t you think that, in their struggle to detect similar words and passages, they impose restrictions on our privilege to create knowledge and culture, to reinterpret the world to describe it in a different, new way?

Because they repeatedly prove to us that what we do is always the same and that our contribution is inconsiderable or non-existent?

And we have seen everything and we haven’t invented anything new.

That may be true. On the other hand, if we are not able to do what machines can do, then why not to trust them? Machines make us realize not only the risks but also the benefits which accrue from that situation. It may turn out that some theses are not even worth supervising.

Will we stop pretending?

Yes. Why would you write 30 theses on division of agricultural land located by the river in a tiny village, if it brings nothing new?

Does that mean that we will move forward?

We will stop fool ourselves.

*Marek Kozłowski – he defended his doctoral thesis in artificial intelligence in Institute of Computer Science, Warsaw University of Technology. He is the head of the Natural Language Processing Laboratory in the National Information Processing Institute, where he leads a 30-people team of researchers and programmers dealing with development of software using intelligent methods of data processing (e.g. Uniform Anti-plagiarism System, chatbots, semantic search engines). His passion includes natural language processing, data exploration and machine learning. He is the author of over 30 scientific publications on semantic text processing and machine learning.

Uniform Anti-plagiarism System in numbers

• 40,000,000 system queries have been sent to indices to find subsets of potential plagiarism sources for the theses surveyed

• 12,000,000 pairs of documents have been examined with TextAlignment methods (comparison of two documents) in the process of detecting potential plagiarized theses.

• 45,000 users has the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System, out of which almost 30 thousand include users that created their accounts directly in the system, and over 15 thousand include persons using their systems at universities

• 40,000 theses surveys have been performed by the system since the beginning of 2019

• 36,300 browser users have used the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System, according to Google Analytics

• 6,000 surveys may be performed by the current version of the system every day

• 450 seconds is the average time needed to analyze a thesis by the system.

• 216 Polish universities have used the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System

• 100 servers constitute a cluster necessary to operate the system. It manages over 30 terabytes (30×1012 bites) of data.

Data for the period from 1 January to 7 March 2019. Big numbers are approximate.

Under the amended Higher Education Act of 1 January 2019 each thesis must be surveyed by the Uniform Anti-plagiarism System before its author is allowed to defend it.

Przeczytaj polską wersję tego tekstu TUTAJ